02 Aug The American Knights of the Polish Sky

There were twenty-one of them. They came to Poland from the faraway shores of America to fight in the sky for a country that wasn’t even theirs. Like true Americans, they had one objective: to fight for a righteous cause.

The twenty-one heroes formed Poland’s most extraordinary air force unit deployed in the fight against the Bolshevik invasion of 1919–1920. Each of them had different motivations to defend the freedom of this foreign country, but what they shared was their courage, their love of liberty, and their determination to fight for a good cause.

The unit was formed in no small part thanks to the efforts of Merian C. Cooper, a veteran of World War I, which had just come to an end. Yes, that Cooper: the filmmaker behind the classic Hollywood movie King Kong. Cooper’s great-great-grandfather fought side-by-side with the Polish-American military leader Casimir Pulaski at Savannah, in one of the key battles of the American War of Independence. Hoping to repay his ancestor’s debt to Poland, Cooper lobbied Poland’s military to to create an air force squadron comprising American volunteers.

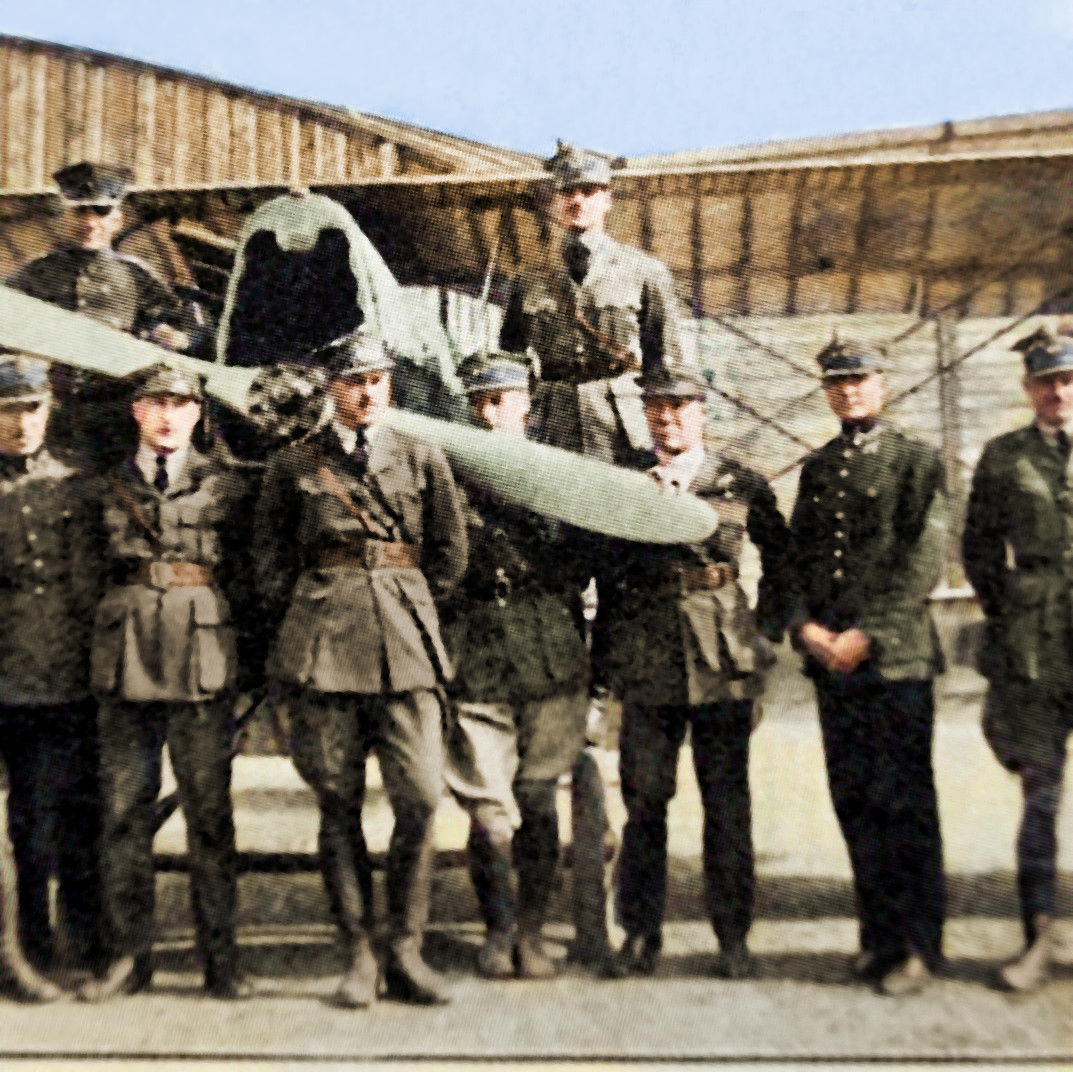

He was joined in 1919 by Major Cedrick Fauntleroy, the future commander of the newly formed squadron and its first eight American volunteers. Their ranks would soon grow to 21 pilots. They were equipped with old but trusty biplanes that Austria had left in independent Poland after World War I, and which had been kept in good repair by Polish mechanics.

In late 1919, Major Cedrick Fauntleroy assumed full command of the squadron, and Merian C. Cooper became his deputy. The squadron was assigned the number 7, and Fauntleroy and Cooper decided that it would bear the name of another Polish-American hero of the American War of Independence: Tadeusz Kościuszko. The unit was officially named the Polish 7th Air Escadrille, but it was best known as the Kościuszko Squadron. It was then that the unit’s famous insignia were designed: a traditional Krakow hat over a pair of crossed scythes against a stars-and-stripes field. The insignia have become an important part of Polish aviation history. The symbol was later emblazoned on the Spitfires flown by the 303 Polish Squadron, and is now the emblem of the 23rd Air Base of the Polish Air Force.

The Kościuszko Squadron was also unique in that it had its own train. It was equipped with special platform cars used to transport planes, along with a military headquarters, sleeping cars, and an on-board mechanical shop. This allowed the American pilots to quickly enter the fray at various stretches of the Polish-Soviet front, striking fear in the hearts of the Bolsheviks.

The squadron fought in a number of locations, bombing Russian positions and reinforcing the defenses of Polish land forces. To the great disappointment of the brave airmen, they saw almost no dogfights against enemy fighter planes, and were instead assigned to daily bombing runs—missions they carried out with equal ferocity.

And then, in August 1920, the 21 brave pilots and their wooden planes faced off against the fearful and ruthless Konarmia, or 1st Cavalry Army, under the command of Semyon Budyonny. On August 16, 1920, the squadron was given the command to stop the enemy. At the time, the unit had only five battle-ready pilots—Fauntleroy, Edward Corsi, Elliot Chess, Jerzy Weber, and Aleksander Seńkowski—but that didn’t stop them. The airmen carried out 18 bombing sorties while constantly strafing the cavalry with machine-gun fire, undermining morale and causing numerous casualties. In just a few days of battle, the squadron’s fighter pilots experienced more than most people do in an entire lifetime. They got a taste of victory, but also experienced the bitterness of defeat.

On August 23, the Soviet front suddenly collapsed, and the attacking forces began to beat a panicked retreat. For the Polish 7th Air Escadrille, the war had come to an end.

General Puchucki of the 13th Infantry Division later wrote in his report: “The American pilots, though exhausted, fight tenaciously. During the last offensive, their commander attacked enemy formations from the rear, raining machine-gun bullets down on their heads. Without the American pilots’ help, we would long ago have been done for.”